Reading Time: 8 minutes

Here’s a contrarian opinion: since COVID started, we’re doing project management all wrong. We’re adapting to a work-life balance that is governed by a different set of social dynamics, but the project management strategies we employ haven’t been updated accordingly.

Due to improved technology and a cultural shift in how we perceive remote work, modern development teams can benefit from adapting some practices of XP, a project management strategy that was initially dismissed when it came out over 20 years ago.

First off, what is XP (Extreme Programming)?

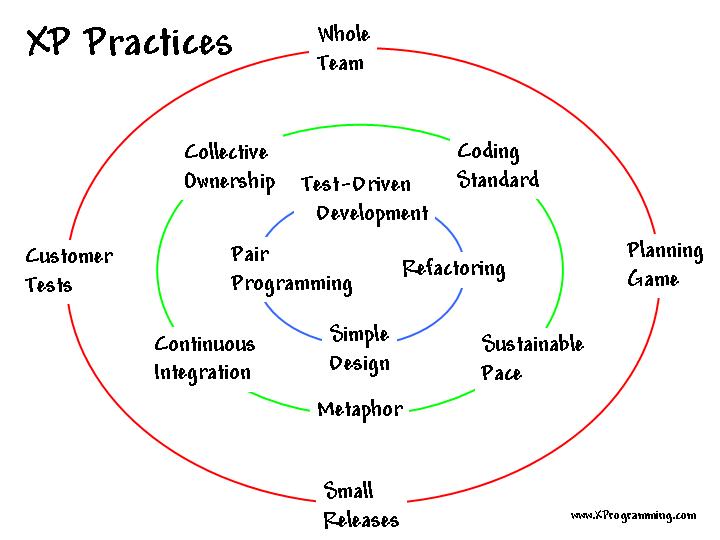

Extreme Programming is a software development style that takes the ideas from the Agile Development process and drives them to their “logical extremes”, which culminate in a set of 12 practices and philosophies. Adopting these practices *should* lead to a productive but sustainable pace of software development. I’ll add a picture of the 12 practices below, but I find that this comment on a web forum from 2004 captures the ethos succinctly.

A 30 second history lesson on Project Management

- In the land before time, software teams used a waterfall approach to software development. Most software projects were failures. (See: The Mythical Man-Month)

- In 1995, Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland created Scrum, a process management framework influenced by a 1986 article in the Harvard Business Review by Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka.

- In 1999, programmer Kent Beck released a book called Extreme Programming Explained, wherein he outlines a radically new and different approach to software development.

- In early 2001, the industry’s most well-regarded engineers (including Beck, Sutherland, and Schwaber) met at a famous ski resort and combined the ideas of these frameworks into a new paradigm for how organizations should do software development. That paradigm is the ubiquitous Agile Software Development movement.

-

The Agile movement fragmented as it grew in popularity. Over time, Agile was co-opted by business folks and process-oriented project managers.

- Rigid formalizations of the practices introduced process bloat, which slowed down development teams big and small.

- People began forking off and experimenting with alternative styles of software development, which is where Mob Programming is derived from.

- Kanban, a method developed by Taiichi Ohno for Toyota in the early 1940’s, resurfaces as a viable project management strategy for software systems.

Some methodologies, like Kanban, enjoyed success in some development teams. Kanban became the preferred strategy in DevOps or client-facing support teams, for example, because it allowed teams to allocate effort for unpredictable events that necessitate high urgency fixes.

XP was decidedly less popular. It was in a bit of a limbo — some of the top practitioners in our field were using XP, such as Martin Fowler and Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob). In the end, Extreme Programming was considered too unapproachable for the masses, too unpalatable.

Some practices, like pair programming or test-driven development, seem asinine from a business perspective. Indeed, if you visit the wikipedia page for Extreme Programming, they have a lengthy section dedicated to ”Controversial Aspects” — not a ringing bell of endorsement if you ask me.

Rather than describing each principle in detail and debating its merits (which sounds as boring to read as it is to write), let’s discuss why some of the biggest critiques against this methodology don’t hold water anymore.

Popular but weak arguments against XP

Pair Programming is an inefficient allocation of valuable resources because it limits parallelism in a team

I’ve been working remotely for the past 9 months, and started a new job about 3 months ago. Since then, I’ve spent more time pair-programming than ever before, but I’ve also been able to launch one of the largest, most complex features of my career. Pair-programming is the best substitute we have to colocating in our current situation. I use it for many different tasks, and I do it often.

- I was able to ramp up very quickly on my team’s product, architecture, and codebases. Pivotal Labs, a boutique software consultancy that practices XP, has written a pretty good article about how XP is great system for onboarding new engineers.

- I’ve saved hours of dev time getting unblocked and helping my teammates configure their local environment / IDE. (We’re a polyglot team with front-end, back-end, database, and ETL components). Observing each other and sharing keyboard shortcuts have allowed us to shave off seconds for menial tasks, which add up over time.

- I’ve been able to triage and isolate bugs much faster in pair-debugging sessions, preventing myself from “spinning my wheels” if I’ve been stuck on a problem for an hour or more. The repeated exposure means that swarming on a P0 is often times very efficient because we all understand how other teammates think and we can divide-and-conquer a problem unconsciously.

- As a team, we’ve been able to gather consensus and coordinate much more effectively because a discussion about the spec can highlight different assumptions we have about the same requirements, leading to clarifications and shared understanding about what we’re trying to do. We’re able to pivot and SPIKE on tasks more easily, allowing us to give better timelines to our business partners.

That’s not to say I agree with pair-programming all the time. I need my own space to think about problems, try out solutions, and organize my thoughts so I don’t waste other people’s time when we meet. People work at different paces, and it’s important to have a system that anticipates that. I think this is where most people get pair-programming wrong; they believe we are forced to operate lock-step with our teammates. But that’s not how I’ve found it to work in practice.

Remote pairing is not this formal thing where we have to spend an uncomfortable amount of time in each other’s personal space — instead, it’s like a game of football, where we huddle between plays and strategize before we execute some chunk of work. Sometimes we work on a task together, and sometimes we work on separate pieces.

There’s no better example than in ”Coders at Work: Reflections on the Craft of Programming”. In Chapter 2, Peter Seibel interviews Jamie Zawinkski, an OG engineer of Netscape and a founding member of Mozilla. The whole interview is super fascinating, but I’ll post the part of the interview that stands out:

… [discussion about building netscape 1.0] …

Seibel: At some point you also worked on the mail reader, right?

Zawinkski: In 2.0 Marc [Andreessen] comes into my cubicle and says, “We need a mail reader.” And I’m like, “OK, that sounds cool. I’ve worked on mail readers before.” I was living in Berkeley and basically I didn’t come into the office for a couple weeks. I was spending the whole time sitting in cafes doodling, trying to figure out what I wanted in a mail reader. Making lists, crossing it off, trying to decide how long it would take me. What should the UI look like?

Then I came back and started coding. And then Marc comes in again and says, “Oh, so we hired this other guy who’s done mail stuff before. You guys should work together.” It’s this guy Terry Weissman, who was just fantastic — we worked together so well. And it was a completely different dynamic than it had been in the early days with the rest of the browser team.

We didn’t yell at each other at all. And the way we divided up labor, I can’t imagine how it possibly worked or could ever work for anyone. I had the basic design done and I’d started doing a little coding and every day or every couple of days we’d look at the list of features and I’d go, “Uhhh, maybe I’ll work on that,” and he’d go, “OK, I’ll work on that,” and then we’d go away.

Check-ins would happen and then we’d come back and he’d say, “Alright I’m done with that, what are you doing?” “Uh, I’m working on this.” “OK, well, I’ll start on that then.” And we just sort of divided up the pieces. It worked out really well.

We had disagreements — I thought we had to toss filtering into folders because we just didn’t have time to do it right. And he was like, “No, no, I really think we ought to do that.” And I was like, “We don’t have time!” So he wrote it that night.

The other thing was, Terry and I rarely saw each other because he lived in Santa Cruz and I lived in Berkeley. We were about the same distance to work in opposite directions and because the two of us were the only two who ever needed to communicate, we were just like, “I won’t make you come in if you don’t make me come in.” “Deal!”

Seibel: Did you guys email a lot?

Zawinski: Yea, constant email. This was before instant messaging — these days it probably all would have been IM because we were sending one-liner emails constantly. And we talked on the phone.

--

Even in the early 90’s, engineers were figuring out that this was a good system for remote work! And that’s without instant messaging, video-chatting, and the ability to simultaneously be on the internet and make a phone call.

As the interview may have unintentionally highlighted, having uninterrupted chunks of coder time was a key component in their successful collaboration. The idea has been talked about ad nauseum in the book ”Deep Work” by Cal Newport, and many companies have independently verified that having distraction-free blocks for developers has yielded impressive productivity gains. (duh!)

This is another area where remote teams benefit. The home workspace has different distractions than the office workplace, but provided you can recognize and plan around them, it can be more productive than an office.

For starters, there isn’t as much of an interest or need for idle chit-chat, and distractions such as commuting, birthdays, or firings aren’t competing for your attention. We don’t need to pretend to be busy, because we’re being scrutinized more on our output than our effort.

A side note: Many parents have had to be full-time school teachers and caretakers alongside their work. This approach may not work well if you don’t have the luxury of a quiet workspace. That’s totally understandable.

Continuous Design Approach is inefficient, impossible to measure, prone to getting off track, and “enormously expensive” to customers

Most of these criticisms came from Matt Stephens and Doug Rosenberg, who co-authored a book called ”Extreme Programming Refactored: The Case against XP”. And pretty much on all counts here, they’re totally f*cking wrong.

I don’t want to bash these guys too hard — I mean, they wrote this in 2004, and I have the benefit of hindsight that they certainly did not have. But, in the 16 years since their book was released, the software engineering community has collectively agreed that a Continuous Design Approach (aka Continuous Innovation) is an ideology that not only works, but is largely responsible for the success of many B2C startups in the post dot-com generation (e.g. AirBnb, Facebook).

Eric Reis wrote the seminal book the Lean Startup, making the argument that a continuous innovation / lean approach saves money in the long run because “failing fast and pivoting means you don’t end up building the wrong thing”.

VC investor Peter Thiel gave further praise of Continuous Innovation in his book Zero to One, while Paul Graham, co-founder of the Y Combinator startup accelerator, penned the famous essay ”Do things that don’t scale”. You can see it in the ethos of Facebook’s old company motto: ”Move fast and break things“.

It’s not just VCs and founders talking about it. Edmond Lau, in his book the Effective Engineer, discusses tight-feedback loops and continuous delivery as the flywheel that powers the knowledge-discovery engine, which enable developers to iterate quickly and create leverage on their projects.

And finally, Google Ventures has published their own guide for applying a Continuous Design Approach to their sprints. This guide struck a chord in the HCI / UX space. GV’s design sprint bears striking resemblance to the company IDEO, which had their own ABC Nightline special in 1999 about re-designing the shopping cart that blew America’s mind. 🛒 🤯

The point is: Continuous Innovation isn’t some fluke. It’s been around for a while, the community collectively agreed it was awesome, and it will continue to stick around.

XP requires too much change to adopt, and can only work with Senior Engineers

The point that “XP only works with Senior Engineers” relies on the premise that XP is a high-discipline mental framework, and so only wizards can pull it off. Ordinary people are creatures of habit, so after the first major speed bump, XP falls apart at the seams.

But, this point was made in 2004, where the technology and tooling to automate these tasks simply didn’t exist. It may have certainly been true then, but now almost every modern software company has some sort of CI / CD process like Jenkins or CircleCI. Tasks like linting, unit tests, artifact building, and deployment are handled automatically. (It’s worth noting that unit testing was a “new” idea introduced in Kent’s book, and now we take for granted how it’s a cornerstone of modern software development.)

But that’s not the only technology improvement that makes XP more appealing now:

- Git has made branching and interleaving work across different developers trivially easy.

- Jira, Asana, and other project management tools have matured considerably, allowing us to track and plan our work in smaller increments.

- Slack allows us to communicate asynchronously with each other and receive notifications from application monitoring systems (e.g. Signal / DataDog), so context can be shared broadly and engineers can tackle problems quickly. (“Collective Ownership”, “Whole Team”)

- Designers and Product owners do user-experience interviews, incorporate product metrics tracking, and collect NPS surveys, allowing us to get feedback from the client without actually needing them to be on-site.

These technologies reduce our need to have a disciplined process to accomplish these tasks. Having less to worry about makes it easier for us to concentrate on doing the rest of the principles well.

XP’s practices are interdependent but few practical organizations are willing/able to adopt all the practices; therefore the entire process fails.

We’ve already adopted the majority of these practices without realizing it! Times are different, technology is different, and many of the radical concepts introduced by XP are conventional wisdom nowadays. The nature of work is evolving as we speak; we shouldn’t be scared to challenge our assumptions.

As with all things, XP is not some magic bullet. There are aspects that were developed 20 years ago that haven’t stood up to the test of time. My goal with this essay isn’t to convince you that XP should be adopted in its entirety; but rather it should be investigated and each team should cherry-pick the parts they like.

Parts of XP I don’t agree with

- Planning Game: our team follows a lightweight agile/scrum process and that works well for us. Sprint Planning, Sprint Grooming, Sprint Retrospective. That’s it. The Planning Game introduces a lot of new cycles, and it’s not clear what the benefit is in having these discrete layers.

- Test-Driven Development: I know that TDD must work for some people, but testing in software development has come a long way, and there are multiple strategies for how to incorporate tests in your software product successfully. Additionally, I work in Python and JavaScript (2 dynamic languages), and oftentimes, I can avoid the “big upfront design” by prototyping very quickly in a repl or jupyter notebook. TDD was developed with Java in mind, which lacked these capabilities.

If you’re interested in experimenting with how XP might fit with your team, here are a few suggestions for how one could do that.

How to (slowly) integrate XP into your team’s workflow:

- Watch this talk by Dan North called ”Patterns for Effective Delivery”. Pay special attention to all the strategies he lays out: (Ginger Cake, Dancing Skeleton, Spike & Stabilize). This talk has influenced me the most in my career, its 45 minutes of poignant insight-after-insight. If there is one thing a person should take away after watching this video, it’s what working on an XP team should feel like.

- It’s time to wash ourselves clean of our unhealthy obsession with time-based planning. Watch this video by Allen Holub on the #noestimates movement to get an appreciation for a different take on how engineers can control the Agile process. I’ve had mixed results with #noestimates, but it does provide food for thought.

- Coming off the heels of that, our team recently put a practice in place where we continue to break down tickets until every task can be done within a day or two max. As a result, we don’t need to do “story point estimations” during grooming — we just focus on clarifying tickets we know very well, breaking down big initiatives into bite sized pieces, and creating spikes for discovery based work. Bye bye, fibonacci-scale pointing method! 👋

- Take the time to observe the the team’s culture with respect to ad-hoc video calls. This is where we can make the most gains in our remote environment. We need to build a culture within ourselves and our teams where it is OK to pair for 5 minutes on a bug or sync on some product spec. It’s important to be respectful of each other’s time, but we shouldn’t sacrifice team alignment and group intelligence for the sake of inconveniencing each other.

- When you do grooming or sprint planning meetings with the team, take care to observe what items are high-risk. What are our known-unknowns? How familiar are we with the task? If it feels like we don’t already have the solution in mind when we’re discussing a ticket, treat this as an opportunity to do a SPIKE. Remember, it’s totally fine to not know how a project will end up when we’re still in the beginning phases. Expect to have curve balls thrown at you. Spike and de-risk things as they come up. It’s ok to come up with Spike’s mid-sprint if you hit a blocker and need to pivot. Velocity Planning, all that stuff — they’re just means to an end. Nothing matters as much as actually shipping a good, working solution.

- Do regular retrospectives where we reflect upon how efficient and productive we feel as a team. Try new ideas to improve our process. Get rid of things that don’t work. Try to use some proxy for quantitative progress as well (Jira Tickets closed per sprint, or number of features launched). Use this is a feedback loop to determine what your team’s optimal workflow is. Every team is different, at the end of the day XP is as much as shift in perspective as it is a process for doing software engineering.

I hope you enjoyed the essay, thanks for reading! If you have any comments or responses, just tweet me @nudgemybody!

Further Reading:

- Coders at Work: Interview with Jamie Zawinski

- Gitlab playbook on remote work strategies

- Stripe’s reflection on creating all-remote hub 1 year later

- A recent take on remote mob programming (2018)

- An Introduction to XP

- Industrial XP: Making XP Work in Large Organizations

- When Is Xp Not Appropriate

- Wikipedia: 12 Practices of Extreme Programming

- https://toggl.com/out-of-office-remote-company-culture/