Reading time: 12 minutes

This is the first post of a 3 part blog series focused around improving our interviewing practices as a development community. Check out the other parts, too:

- Part 2: Evaluating the Alternatives to LeetCode

- Part 3: A sane and fair process for conducting Senior Software Engineering Interviews

The bane of every software engineer’s existence — if there is one — has got to be interviewing. For reasons unbeknownst to me, engineers every day are subjected to draconian LeetCode style interviews, for which nothing short of a slam-dunk success means failure and eventual rejection from the company.

The Interview, explained

(feel free to skip this section if you’re already familiar)

For the uninitiated, these LeetCode interviews are designed to test an engineer’s “fundamentals”. They place a particular emphasis on using less common data structures or algorithms — stuff most programmers haven’t studied since college — usually paired with a “trick” to make the problem more difficult. Here’s the breakdown of a typical 1 hour long interview:

- The interviewers spend 5-10 minutes introducing themselves, and ask the candidate to do the same

- The interviewers may engage in a few behavioral questions, taking ~10-15 minutes. This is often skipped or done at the end.

-

A programmer is presented with a logic / programming problem. They are usually given anywhere from 25-50 minutes to:

- Analyze the problem and determine the optimal solution (by figuring out the trick, correct data structure, and algorithm)

- Write it up on a whiteboard with no errors

- Explain their answer to the interviewers

- Modify their solution to solve additional constraints by their interviewers

- Interviewers allow anywhere from 0-10 minutes for the programmer to ask the interviewers questions about the company.

Why the Interview is structured this way

Having interviewed a good number of candidates myself, it’s straightforward to understand what’s being tested in each phase of the interview.

The introduction and the behavioral questions are designed to get a sense of culture fit with the candidate. Interviewers are trying to break the ice and observe the candidate’s ability to communicate / gel with the team.

Cool, makes sense. With the technical portion of the interview, the interviewers try to get enough signal to judge the candidate’s ability to:

- code in a language of their (or our) choosing,

- analyze and solve a problem

- demonstrate knowledge of data structures, algorithms, testing, and coding best practices

- communicate their technical thought process effectively

- work under pressure

The last part of the interview is for giving the candidate some time to ask questions so the interviewer can pitch the company favorably to them (aka make them drink the Kool-aid).

A candidate will have to do this anywhere from 2-6 times for just 1 company. You may be thinking, “that’s not so bad”, but consider this: my last interviewing cycle lasted around 4 months, and I had repeated this process with 30 companies. That’s a lot of interviews (not counting practice interviews), all following the same routine.

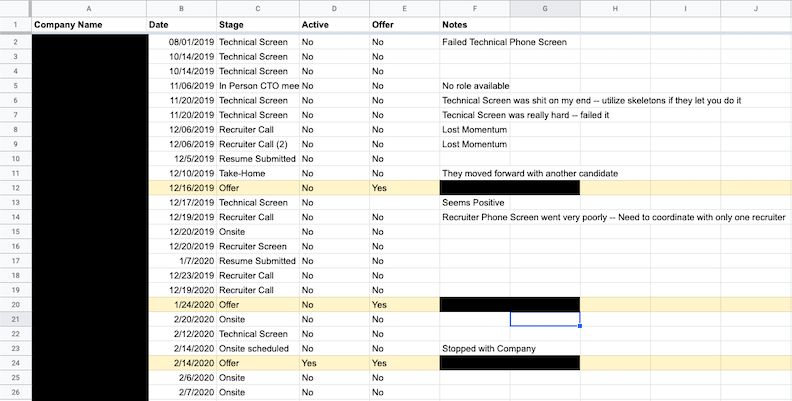

A screenshot of my most recent interview cycle

Interviewing with so many companies, however, provided me a wealth of data points: I could observe the different strategies companies employed. Not every company copied each other — some companies gave much better interviews than others. But before we discuss some of the approaches that worked really well, let’s understand why we continue to administer LeetCode interviews for candidates.

What are the benefits of LeetCode Interviews?

The world is not black and white; there are a few reasons why companies and candidates prefer LeetCode interviews.

Companies are on a constrained timeline and budget to conduct interviews. Interviewing is costly, so companies look for ways in which they can maximize the signal of a potential candidate without wasting too many resources on a “dud”. Many companies believe that the most damaging thing that can happen to a company is hiring the wrong person (thankfully, some do not). In this vein, interviewers are encouraged to pass over potential “good” candidates until they find their one “great” candidate. LC style interviews provide a quick and easy, binary decision making process. “Did the person solve the problem? No? OK then, let’s move on.”

The second benefit is that for junior engineers, this type of interview is still the best. Most recent graduates have never been exposed to modern software development practices, because academia often lags a decade or two behind the industry. When I got my first software internship, I didn’t even know how to use git. I had only coded in C and in Java; Python and JavaScript weren’t taught at my university. My databases class taught me about B-trees, not how to use Mongo. As for the alternatives: Either you skip the technical portion altogether (which is uncommon), or you make the candidate do a take-home, in which they will need to spend a disproportionate amount of time reading documentation or understanding how a basic web request is made.

Finally, there is a widely-circulated, but disingenuous belief that the engineers who can solve these LC problems are either hard workers who prepared adequately and take their career seriously, or naturally gifted problem solvers. The former represent the aspects of hard work and grit (“the ideal worker”), and the latter embody the traits of a mythical 10x engineer. In either case, these engineers will be a boon to your organization, so it makes sense to wait for one of these people to show up so you can reap the benefits.

What’s wrong with these interviews

They are not a proxy for everyday development

First and foremost, they do not resemble the work an engineer performs on a daily basis. With 100% certainty, I can say that I have NEVER needed to use a heap to solve a real-world programming problem, nor has iterating through an array in reverse order helped improve the efficiency of an application I wrote. The one time i had to implement a distributed LRU cache for the company, I used a library for the bulk of the work. These kinds of problems don’t exist in modern day software engineering because the commoditization of powerful tools and platforms (like AWS), coupled with the availability of hardware resources in modern computers, make these performance tricks negligible.

The opposing argument is that while developers nowadays have a cornucopia of libraries and tools at their disposal, it is still critical to know how these tools actually work under the hood so that the engineer can make judicious decisions about what tool is appropriate for the job, and in what capacity. Fair enough — I concede that knowing the nuts & bolts of how an algorithm or data structure works allows you to make better informed decisions in your work, and that being good at abstract thinking makes concrete tasks easier.

But then, why do we insist on adding “tricks” to our programming problems? If we really only cared about knowledge of data structures, shouldn’t we just ask someone to implement a Binary Search Tree in front of us, talk about the characteristics and runtime properties of that tree vs other data structures, and then call it a day? Couldn’t we judge their knowledge via a behavioral interview, asking them about a time where they used a few design patterns and data structures in concert to model a problem effectively?

It’s also worth noting that one of the most popular problems on LeetCode actually advocates “breaking the rules” and committing a programming faux-pas (overwriting state in the passed in matrix) in order to get the optimal solution. You shouldn’t expect that a candidate, in 25-40 minutes, should consider breaking a tenet of good software engineering in order to solve a problem more efficiently. That’s not really fair, is it? Nor is that something that you would encourage them to do if they were working on your team, because they would be leaving a trail of state-related bugs everywhere they go.

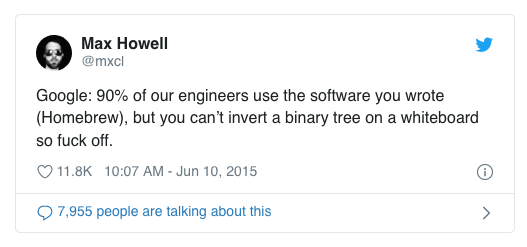

If the creator of homebrew (who wrote the software installed on practically every developer’s macbook) is having difficulties interviewing, then maybe this isn’t a good measuring stick of skill

The difficulty of the assessment does not scale correlate with actual experience

The most frustrating thing about LeetCode interviews is that an individual’s work experience does not transfer at all to their ability to LeetCode. It’s not like I’m able to breeze through Medium and Hard problems now that I’ve spent some time in the industry. This is the most dishonest part of the interview process — that we tie the expected rigor of the role to the difficulty of the LeetCode assessment. Without exaggeration, I was given a LeetCode hard question during the phone screen for Brex’s Data Engineering position.

Engineers who have considerable experience in the industry should be judged by criteria that determines the value of their experience. Senior Engineers need to know how to code and be damn good at it, and the coding assessment needs to reflect that. This is easier said than done, and because this is nearly impossible to test within an hour time frame, we resort to LeetCode.

However, being good at LeetCode assessments feels like an adjacent skill to writing software. You still need to be good at both in order to have upwards mobility in this industry, but you won’t actually get better at it by accruing experience on the job.

They cram too much into too small of a time-frame

So, enough with the moral qualms about the interview; let’s discuss the structure. I noted above how the typical interviewing process works, and the interviewer’s intentions at each stage. While its admirable to try and evaluate each of these important aspects, it’s unreasonable to think that one or two interviewers can accurately glean this information in a single hour-long interview. This is why some interviewers can wildly disagree with each other about a candidate’s skill.

Whats the accepted solution? Let’s have a whole suite of engineers rapid-fire interview the poor candidate (who is probably sweating profusely right now in the conference room you left them in)! The law of averages will save us! If we all agree we like this candidate, then let’s let her pass. But if one of us didn’t get a good vibe? Well, “its better to pass on a good candidate than hire a bad one”, so it’s sayonara and good luck to you.

There’s no clearer example of this than Amazon. Amazon’s interviews are notably different than other FAANG companies because they try to cram both the technical and behavioral components in the same 1 hour interview. Before the interview, you’re asked to memorize the Amazon Leadership Principles, and during the interview, you’re asked to regurgitate them in some prefabricated story using the STAR format. Because there is a time crunch for interviewers, and the technical aspect is already time consuming, the interviewers race through the behavioral part. You can make up whatever answers you want (as long as they fit the mold); they won’t have time to ask legitimate follow ups anyways. The moment you say the buzzword for the Leadership characteristic they are scanning for, you can see them check off that box in real-time.

Fred Brooks is famous for saying that “Adding manpower to a late software project makes it later”. How’s that old, tired joke about project managers go?

Definition of Project Manager: A person who thinks 9 women can deliver a baby in 1 month.

Oops. In the Software industry, we have a habit of over-extending our resources and delivering sub-optimal solutions. We’re doing the same thing with our interviews.

Depending on the interviewer, you are rewarded little to no credit for communication, problem solving, or coachability

Many interviewers pay lip-service to the idea that candidates should be judged holistically, but then proceed to judge them by very strict standards. It’s not enough to articulate your approach, code a solution, debug, and iterate in a real-life manner. If you get stuck and ask for hints, you get docked points. If you don’t solve the problem the way your interviewer wants you to solve the problem, your solution is considered “messy” and “confusing”. A sub-optimal solution? “Lacks Problem Solving Skills”.

Having someone coach you to a workable solution means the highest score you can expect to get for the interview is a “Neutral”. We don’t observe the process of problem solving and judge based on that — we only reward people who get it right.

They benefit only a small class of software engineers

Let’s talk about the kinds of people who benefit from this kind of interview. Off the top of my head, I can think of two major groups: competitive programmers, and/or younger candidates who studied computer science recently in college and have no family obligations.

Think about it; would someone have the same chance of success if they didn’t have the same amount of time to prepare as the groups listed above? Probably not. So what about the person who is starting a family? What about the bootcamp graduate who hasn’t studied computer science theory? Or the engineer with 10+ years of experience? You have to put in a serious amount of work to learn or refresh these concepts. And people wonder why ageism is such a large problem in the software industry. Companies that rely solely on LeetCode style interviews cannot be considered “diverse” if their recruiting practices disproportionately discriminate against certain kinds of candidates.

This points to an obvious problem: If people don’t have the means to be able to work on these esoteric exercises in their personal time, how do they study?

One way is to quit your current company, take a small break, and then “grind LeetCode” full time until you are ready to interview. In fact, for senior engineers who are considering job hopping, this is currently the best way to get your next job. Well, what about the people who aren’t willing to forego their paycheck in order to study?

Here’s an unspoken “dirty secret” — they do it on the job. They practice LeetCode during their work hours, often putting off actual work in order to train. This is something I’ve observed in the workplace in almost every job I’ve had, and something I’ve done as well from time to time.

How did these interviews get so popular?

By this point, I hope we can agree that LC interviews are not the panacea we make them out to be. But why are they so prevalent? All roads point to FAANG (FAANG => Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Google). Since the early days of the internet era, companies like Microsoft, Yahoo, and other FAANGs have been employing these kinds of interviews in order to screen out as many applicants as they could. Part of this is logistics — the harder the interviews, the smaller the pool of contenders, which allow companies to make hiring decisions more quickly.

The less obvious reason was that it was good for the brand. Like McKinsey, companies could improve their own image by generating applications that it could then reject, to establish its own eliteness. Hence why we believe in this assumption that good candidates aren’t actually “good enough”, and why we need to only hire “the best” and have “bar raisers” to continually set higher expectations for our applicants. And by golly, wouldn’t you know it. Every fresh-faced grad wants to eventually work for a FAANG because we’ve all been conditioned to think that working at a company at that level represents the apex; that we can really, finally shake off this imposter syndrome and call ourselves “good engineers”.

Another reason is that this opened up a huge market for enterprising individuals: Cracking the Coding Interview, LeetCode, and the market for self-help guides began to boom. Not only did this add to the mystique of these FAANGS, it also meant that your original “hard” questions would become well-known given enough time. Now, we are in a rat race to “re-discover” new facets of computer science theory to test our candidates on. New questions means new editions of the book, renewed subscriptions for LeetCode, interviewcake.io and the like. It’s not a coincidence that Dynamic Programming problems have become more popular recently (which they teach as a class at Georgia Tech’s grad school program, no joke). It’s a self-perpetuating machine.

Finally, for the average joe or jane that gets into a company based on their LC performance, some of them fall victim to their confirmation bias. Well, because they made it, everyone should make it to be considered “on the same level”. They begin to view themselves as upholders of meritocracy, and pride themselves on being considered a “tough interviewer”. Sadly, I think I fell into this camp for a long time. The toxic behavior of gate-keeping is very much enabled by this style of interview. It’s important to clarify that this exists in other styles of interviews as well, but it seems especially rampant with LeetCode interviews.

What should we be testing for to satisfy our goals when interviewing?

Let’s take a step back, and consider what our goals are (as interviewers) when we do this type of interview. Many companies offer a rubric to their potential candidates in order to help them perform well on the upcoming assessments (by the way, if your company does this, kudos to you!). From this, its pretty straightforward to glean what criteria is used to judge candidates:

- Problem Solving: Given a problem, can the candidate think on their feet and come up with a solution? Are their proposed solutions reasonable, and can they leverage their experiences effectively? Are they coachable, and can they work well with feedback?

- Raw Technical Chops: Can this person actually code at a reasonable speed? Are they familiar with the language’s standard API? Are they familiar with Data Structures and Algorithms?

- Design Patterns / Coding “Style”: Does this person write clean code? Do they use descriptive variable names, and appropriately sized functions? Do they display other hallmarks of maintainable software?

- Communication / Behavioral: Is this person effective at explaining what they are thinking about, and describing a solution that can be understood by others?

- Attitude / Demeanor: Is this person a brilliant jerk? Are they stand-offish? Cocky? Are they independent? Are they low-energy? Is this someone I can see myself working with? Does their values align with our company credos?

For different companies, the weights we associate with each of these categories might be different, but ultimately, if a candidate gets a pass on all these categories, they would most likely be extended an offer. And these are all fine criteria — it’s just that our current process for evaluating this criteria is a little flawed.

So what’s an engineer supposed to do? Despite all this LeetCode hate, I still believe there is a time and place for them, but not in the way we currently use it (and not nearly as much). What are our alternatives? Read on to find out:

Part 2: Evaluating the Current Alternatives to LeetCode

Thanks for reading! If you have any comments or suggestions, please tweet me: @nudgemybody